The origin of the cult of Mithras, between the Eastern and Western worlds

Mithras, also called Mitra or Mithra depending on the historical period, region or language, is one of the oldest known Indo-European gods.

Mithra is one of the most remote Indo-European divinities, member of the known pantheon and common between northern India and Iran. The first document found that mentions its name is from the second millennium B.C. It is a clay tablet from Boghaz-Köy, in present-day Turkey, which was the ancient capital of the Hittite Empire. In it, Mitra is invoked as guarantor of an agreement established between the Hittites and a neighboring people, the Mitanians.

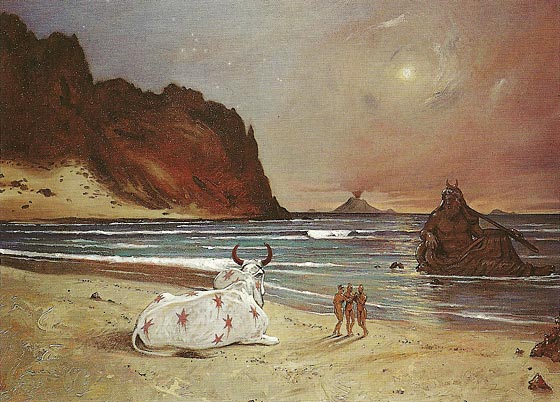

Chiaro di Luna – Massimo Livadiotti

The term Sanskrit Mitra, like the Iranian Zoroastrian Mithra, comes from the hypostasis Proto-Indo-Irania *mitra, which means contract. In the Indian subcontinent, Mitra is the protector of honesty, friendship, as well as contracts and meetings. Mitra is one of the figures appearing in Rigveda where he is intimately associated with Varuna.

In the Iranian tradition, since the reform of Zarathustra, Mithra (Miθra) is considered a yazata, i.e., a divinity, of the covenants and of the given word. By extension, Mithra is the protector of truth, among other functions of agrarian origin.

The term Mithra evolved into Mehr, Myhr, from which the current Mihr in Persian is derived. The tenth Yasht of the Avesta, the Persian sacred text, is entirely dedicated to him and defines him as "Mitra, the lord of broad pastures, with a thousand ears, a thousand eyes, a Yazata invokes him by his own name [...]".

Later, Ahura Mazda, the supreme god, reveals to Zarathustra: "Truly, when I created Mithra, the lord of broad pastures, or Spitama! I created him as worthy of sacrifice, as worthy of prayer as I myself, Ahura Mazda". Since then, in the Zoroastrian calendar, the sixth day of the month and the seventh month of the year are consecrated to him, of which Mitra/Mihr is protector.

The origins of the Roman Mithras

There is no absolute consensus among researchers about the origins of the Roman cult of Mithras, formerly referred to as the Mysteries of Mithras. According to Franz Cumont, the first modern scholar to focus on this cult, it was a Romanised form of the Mazdeist or Zoroastrian religion. Cumont, following the trail left by Plutarch (Pompey, 29), stated that pirates based in Cilicia, now southern Turkey, were practising the Mithraic cult as early as 60 BC. They were sent by the thousands as slaves to Italy, from where their beliefs spread to the rest of the European continent. However, there is a lack of documentary evidence to confirm this hypothesis. Another theory is that the cult was imported with the troops that fought in Greece and Asia Minor during the Mithraic Wars of the 1st century BC, but here too there is no consensus.

Other contemporary researchers, such as Roger Beck or Reinhold Merkelbach, have suggested that the cult was created in Rome. In this case, clerics or high officials with a wide knowledge of Iranian culture, as well as of Greco-Roman religion and philosophy, would have created something new. In this sense, Manfred Clauss affirms that "Mithras, identified with Helios, the Greek solar god, was one of the gods of the synthetic and real Greco-Iranian cult created by Antiochus I, king of the small but prosperous state of Comanege, in the middle of the 1st century BC". In the opposite range of theory, J.R. Russell argues that "it is out of ignorance that some current writers propose as definitive other solutions to the question of origins - a solution that completely excludes the Iranian religious component at the centre of the doctrines of worship".

David Ulansey, for his part, from a "creationist" point of view, revisits the mysteries from an exclusively astrological point of view. In this case, Ulansey claims that the mysteries obey the discovery of the phenomenon of the precession of the equinoxes by the Greek astronomer Hipparchus of Nicaea.

As is usually the case, the truth is most likely to be found at an intermediate point between the hypotheses that have been put forward over time. As a syncretic religion, the cult of Mithras cannot be reduced to a purely circumstantial expression that excludes the many evidences from other Indo-European regions.

Mithras in the Roman Empire

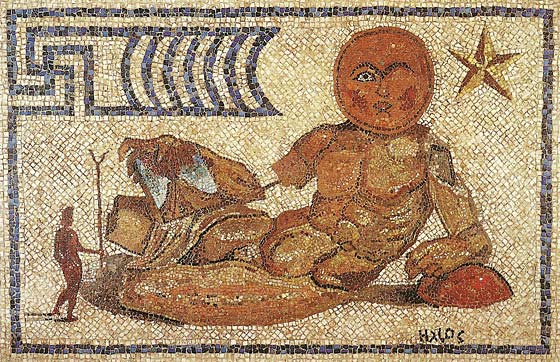

Helios – Massimo Livadiotti

The practice of mysteric cults had been known in Rome since ancient times thanks to the Hellenistic world, where the Eleusinian mysteries enjoyed great prestige. Later, the Romans adopted the Phrygian goddess Cybele, as well as Bacchus-Dionysos and Isis. The earliest record of Mithras in the Roman world is found in the late 1st century Thebaid of Statius, where the Latin poet writes "Mithras, who, beneath the rocks of the Persian antechamber, twists the horns of the reluctant bull". The first archaeological evidence relating to Mithras dates from the same period, around 98-98 AD. It is a relief of the solar god killing the sacred bull consecrated by Alcimus, slave of T. Cladius Livianus, prefect of Trajan. Still, the state of evolution of the cult of Mithras at that time is unknown.

The Mysteries of Mithras reached their peak between the 1st and 4th centuries AD. The role of the Roman legions as a source for the spread of the cult in different areas of the Empire has been confirmed by the presence of temples and other monuments devoted to Mithras in the camps of the Limes and in settlements of a clearly military character. Roman legions accompanied the spread of the cult of Mithras in areas such as Thrace and Crimea, North Africa, Britain and Dacia.

The development of the cult in military settings indicates the special interrelationship between Mithras and the Roman legions. The presence of this cult in rural areas was rare, with the exception of some sanctuaries built in private villas, sometimes of considerable size, such as the Vil·la dels Munts, Spain. In many urban settings the wealth of evidence suggests that social groups other than the military were also involved in both the cult and its spread throughout the empire. In this sense, we must take into account the role that merchants in the region of Asia Minor may have played, since their own mobility may have promoted the propagation of the cult of Mithras from the 2nd century AD onwards.

This hypothesis is based on the abundance of epigraphic testimonies where the Greek-Eastern origin of the dedicatees is evident. This has led us to believe that on many occasions it may have been these merchants of eastern origin who brought with them the practice of worship and introduced it into those areas where they settled to exercise their economic activity. This could explain the presence of Mithraea in areas where the military element was quite weak or practically null.

Finally, we cannot forget the abundant presence of other freedmen and slaves, and the role they could also play in the propagation of the cult.

To know more

- Monique Zetlaoui. Ainsi vont les enfants de Zarathoustra. Imago, Paris, 2003.

- Zaraθustra, Avesta: Khorda Avesta. Mihr Yasht (Yast 10) (Himno avéstico a Mitra).

- Israel Campos Méndez, Elementos de continuidad entre el culto del dios Mithra en Oriente y Occidente. Universidad de las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas, 2001.

- Israel Campos Méndez, La aparición de los misterios mitraicos en el marco religioso del imperio romano. Prensa Canaria, Las Palmas.

- Julien Ries. Le Culte de Mithra en Iran. ANRW, Berlín, 1990.

- Joseph Decreaux. Le Culte de Mithra en Orient. Archéologia, Dijon, 1989.

- Emile Benveniste, Mithra aux vastes pâturages. Société Asiatique, Paris, 1960.

- Charles Autran, Mithra, Zoroastre et la préhistoire aryenne du christianisme. Payot, Paris, 1935.

- Roger Beck, Mithraism. The cult of Mithra as it developed in the West, its origins, its features, and its probable connection with Mithra worship in Iran. The Encyclopædia Iranica, 2002.