The Golden Chain of Initiation: Orphism, Eleusis, and Mystagogy—A Reinterpretation

Orphée ramenant Eurydice des enfers, by Camille Corot (1861).

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston / Public Domain

Dear Colleagues,

Having recently joined this forum, I intend from time to time to contribute studies devoted to the mystery traditions of the ancient Mediterranean, with particular attention to the Greco-Roman world. My approach will consider these cults through the intersecting perspectives of philosophy, theology, and what may cautiously be termed mysteriosophy—that is, a reflective attempt to understand not merely the external rites but the religious and metaphysical structures that underlie them.

The mysteries of antiquity are often described as lost traditions; yet this judgment is only partially accurate. Their ritual forms have vanished, but their Platonic types are living, whilst symbolic tokens remain preserved in myth, literature, philosophy, and material culture.

When read together, illuminating each other, these sources suggest a coherent theological superstructure: a religious anthropology, a cosmology, and a soteriology centered upon the transformation of the human souls. What late antiquity described as the Numen multiplex—the manifold divine reality evoked by Vettius Agorius Praetextatus (320 CE - 384 CE) and—should therefore be understood not as a relic but as a continuing intellectual and spiritual horizon. The ancient rites sought to reconsecrate the human person, sacralizing mind, heart, and personal daimonic identity through participation in divine order.

Quoting Musaeus, father of Eumolpus—who, according to legend, founded the Eleusinian Mysteries between 1397 BCE and 1373 BCE—“all comes from one and is dissolved in one.” By this paradigm let us grasp a single method in the interpretation of the mysteries and attempt to discern their common tone and syntax. Following the Parmenidean theory of archē, everything in the world possesses a universal denominator, a great foundation from which all else derives. In Orphic belief, Time as a power existed a priori; the world was born from the cosmic egg generated by Aether and Chronos—in other narratives from the mingling of two Titans, and in others from Erebus with winged Night in Tartarus. The one who hatched from that egg was called Protogonos-Phaethon, son of the immense Aether. Protogonos is understood here as the generator of the cosmos and of all places from the beginning of the world. When he was born, Aether separated from the vast abyss. Kronos (“the striking intellect”) and Ouranos represent the divine mind acting upon primordial matter (eonta), thereby producing the first beings. Kronos is a generative sequence; Ouranos is the stage of the universe in which Mind defines the nature of the elements. Thus the divine Nous permeates the entire world through diairesis, division. Another name derived from these divinities, alongside Protogonos, is Phanes—the first god who generated the totality of the cosmos and subsequently began to encircle it. Plutarch maintained this view with regard to the Orphic Rhapsodies. Aether in Euripides’ Helen is invoked by the priestess Theonoe during a procession of women bearing torches: “May the fires purify the aether, according to sacred law, that we may receive the pure breath of heaven.”

Heraclides of Pontus, following the Pythagoreans, asserted that each star possesses its own world; every star is a separate cosmos. How, then, should one read the luminaries of the firmament with a wise and steady gaze? Sacred words, proclaimed in the disclosure of secrets, gave meaning to the human voice, a breath transformed into song that endured in a holy hymn accompanied by lyres, like the breath of Osirian stars tuning entire worlds which, harmonizing with one another, produced extraordinary music. Were the hieroi logoi written down? Little is known of such legomena—texts read during rites—apart from legends that Orpheus inscribed a tablet placed at the oracle of Dionysus on Mount Pangaion; others claimed it was found near Mount Haemus. Thus human destiny intertwined with heimarmene, supreme fate; there was discovered an image reflecting hermetic mysteries.

Who was Orpheus? Legends proclaim him the son of a Thracian king and the Muse Calliope, a pupil of the Idaean Dactyls, and a hierophant and teacher of the initiations of Dionysus. Orphism, as a soteriological mystery aimed at liberating the soul in a great ascent, was primarily expressed through words. Socrates remarked that, as in Dionysian traditions, the Orphics treated the body as a sarcophagus of the soul; he also warned that many carry the thyrsus (the ritual staff), yet few are mystics—the latter are the true philosophers. Aristotle claimed the Orphics believed the soul was born from the wind—perhaps a breath of the cosmic soul drawn from the world and inscribed into the animal realm. The sacred goal was the transmutation of the soul so that it might become perfected and beautifully attuned to the divine worlds. Macedonian tribes believed their souls first dwelt in animals before settling in humans. Such beliefs suggested a natural initiatory sequence: the rectification of animal souls, then human, and finally semi-divine, provided the chain was not interrupted or obscured by ignorance and forces hostile to this golden chain. Hence two lines of time appear: one marking the beginning and end of the world-soul’s participation in the cosmos, and another linear development of beings within it across the universe’s diversity.

Legend states that Orpheus, priest and bard of Dionysus, altered his mode of worship by raising his hands toward Apollo—the one not manifest in multiplicity—on Mount Pangaion, thereby abandoning his master. In revenge, if one believes in divine passions, Dionysus sent the women, the Bassarai, who, jealous and crying “Look! The poet who scorned us!”, tore his body to pieces. They fastened his remains to a tortoise-shell lyre and cast them into the Thracian river Hebrus; carried across the sea to Lesbos, they were discovered by the inhabitants. There Orpheus’ head was buried with honor and a temple erected on the site. Plutarch, priest at Delphi and compiler of sacred texts, argued that Apollo and Dionysus were the same deity, making divine vengeance unlikely—human vengeance more plausible.

Where the sacred master’s blood soaked the earth, a holy Bacchic herb was said to grow, named Kithara after the sound heard during sacrificial burning resembling a resonant lyre. The Muses gathered his parts and buried them at Libethra (or Leibethra), according to Eratosthenes. It was reported that a posthumous statue of Orpheus in that city sweated profusely when Alexander of Macedon set out to conquer Persia. Many Macedonian women were long involved in Orphic and Dionysian rites, called Klodones and Mimallones, Macedonian names for Bacchants.

Not everyone was convinced of the mysteries’ sanctity. In the fifth century BCE Diagoras revealed fragments of the Orphic and Cabiric hieroi logoi and destroyed a wooden statue of Heracles, declaring publicly that neither God nor gods existed. In Orphic imagination such a traitor was tortured in Hades, though his historical fate is unknown. The Orphic Mysteries were esteemed alongside the Eleusinian and Cabiric rites, ensuring their popularity in Athens and throughout Greece.

Who knew the truth? Were there not many priests and prophets—charlatans and self-proclaimed masters—who captured the hearts of the naive and exploited their souls? Their presence mocked the true mysteries and telestia. One, unable to endure his poverty, prophesied a better world especially for himself, yet continued to live in ignorance; a warrior was said to have slain him in exasperation at his contempt for life. Yet each lived in the hope of possessing truth, so confusing conviction with realization that they sold half-truths and lies for profit.

True priesthoods and masters were those who effectively initiated prepared adepts so that the victorious torch might be carried onward and the human soul transformed to join the procession of the gods. Only a discerning master, no longer a fool, could perceive the difference; the fool’s attention is easily seized by an impostor. Doubt and learning, skepticism and faith in realized knowledge and experience—sacrificial commitment to the gods—grow in intensity through theory and effective practice, like bridges and gates to Eleusis. Every mastery and soteriology is individual, requiring years of devotion, arduous labor, doubt, failure, and renewed strength—like playing chess while taming a wild horse in a dark forest, guided by the Muses toward the goal where endurance joins purpose.

In Lacedaemon, Hermione in Argolis, Kore the Savior—Persephone and Demeter Chthonia—were worshipped, while Hades was called Klymenos (“the Known One”). Heracles was believed to have descended to Hades there, and an entrance to the underworld was located near the sacred grove of Demeter. Indeed, katabasis, the soul’s descent into the underworld, was a key ritual inviting initiates into the world of demigods. Perhaps in the Eleusinian Mysteries the figure present among the hierophants was Hades himself in the Epopteion. On Aegina, where Hecate was honored, Orpheus was said to have founded the cult. Alcamenes first fashioned Hecate in triple form—the Athenian Epipyrgidia (“Tower”)—behind the temple of Victory.

The Bronze-Age Mother Kubileya, depicted on Minoan seals, queen of wild nature and akin to Cybele (later Magna Mater), parallels Rhea, mother of the gods. The mysteries of Cybele and Dionysus were related, resembling Thracian and Phrygian Orphic practices. All were ecstatic and orgiastic cults, like the Bacchic, Corybantic, and Sabazian rites.

Entries in the Byzantine Suda (10th century) suggest Orphic works included Cosmic Cries, Night Hymns, Oaths, Purifications, The Descent into Hades, and Sacred Discourse (the last attributed to the Pythagorean Cercops), among many others. Iamblichus (3rd–4th century CE) stated that Pythagoras drew inspiration from Orpheus in his treatise On the Gods.

The mythic cosmogony of Dionysus-Zagreus contains a mystery of triple birth: from the mother, from Zeus, and rebirth after dismemberment by the Titans and reconstitution by Rhea. Plotinus held that human souls reflect Dionysus’ soul: they fall from heaven yet ascend intellectually toward it; though immersed in nature, their “heads” remain in the heavens, and Zeus established an unbreakable bond granting moments free from corporeality in which they reunite with post-mortem wholeness. Human action resembling the Titans is transgression; proper conduct is Dionysian, awakening the divine element within.

The term oistros, usually associated with Bacchic frenzy, appears in the Orphic Hymns and relates to primordial “titanic” human nature marked by cannibalism and violence. It exists in every person but is restrained by education. Damascius mentions tartarosis, the greatest punishment in cosmic hells awaiting those who behave like Titans. To become Dionysioi one must cast off the yoke of the Titans.

Orphic “gold tablets” buried with the dead instructed them to avoid the river Lethe, gain passage from guardians with the password “I am a child of Earth and starry Heaven; my race is heavenly,” and drink from the lake of Mnemosyne—identified with a-letheia, truth. Some tablets refer to post-mortem deification. A few mention Eukles (an epithet of Hades, “beautiful glory”) and Eubouleus (an epithet of Zeus/Dionysus, “good counsel”).

At the necropolis of Orthi Petra in Eleutherna (9th century BCE–6th century CE) stood a sacred monument crowned by ten Curetes striking their shields. According to a Euripidean fragment, initiates of the Idaean Zeus were also initiates of Zagreus; as Zeus was devoured by Kronos, so Dionysus was by the Titans. Plutarch compared the mysteries of Zagreus-Dionysus to those of Osiris.

A widespread belief held that human souls returned after death to their stars. In Aristophanes’ Peace a servant asks whether people become stars after death, and the reply affirms it. Astral nocturnal rites appear in the Partheneion ode (mid-7th century BCE) of Artemis Orthia in Sparta during the heliacal rising of the Pleiades: “The Pleiades, like us, wear Artemis’ garments, rising through ambrosial night like Sirius.” Artemis, perhaps from aerotomis (“air-cutter”), was often identified with the moon; the immortals called divine realms Selene, and thus the ethereal moon was the “heavenly earth,” the nearest astral heaven of souls.

Katabatic rites—the descent to Hades—signified mystical death: teleutan (to die) and teleisthai (to be initiated). The soul plunged into a vast oceanic abyss, encountered chthonic forces and a nocturnal sun, endured shifting forms to the cold of Tartarus, and was transformed by a titanic wind into a substance akin to divine air—the path to heaven. The abyssal aether was the gods’ nectar and divine fire their ambrosia. The soul, imprisoned against its nature in a Dionysian sarcophagus, required purification.

Private initiations may have existed: the Gurab papyrus, perhaps belonging to an itinerant priest in Ptolemaic Egypt, suggests such a movement, though its success is unknown.

Did Orpheus become a god, or merely open a path? In Plato’s myth, the hero Er saw Orpheus’ soul choose the life of a swan. Where destinies were woven by the Moirai and souls drank from Lethe, Orpheus forgot his former life. Whether this was metempsychosis into a beautiful animal or ascent to the stars is another story.

Kind Regards,

Mateusz Zalewski-G.

References

- Anthi Chrysanthou (2020) Defining Orphism The Beliefs, the ›teletae‹ and the Writings

- Radcliffe G. Edmonds (III) (2011) The ’Orphic’ Gold Tablets and Greek Religion: Further Along the Path

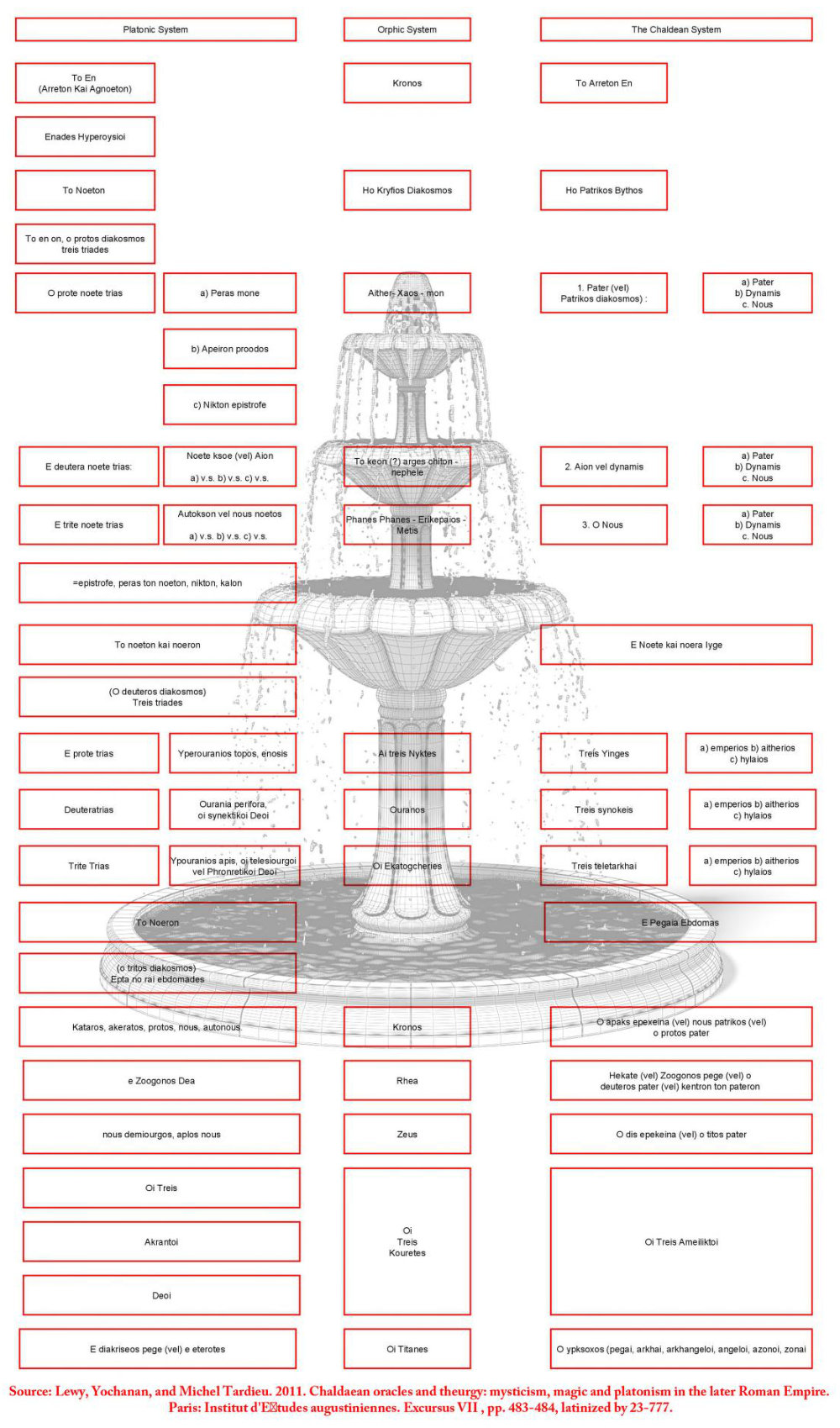

- Hans Lewy (2011) Chaldaean Oracles and Theurgy. Mysticism, Magic and Platonism in the later Roman Empire. Troisième édition par Michel Tardieu, avec un supplément « Les Oracles chaldaïques 1891-2011 »