Re-interpreting the Mysteries of Mithras

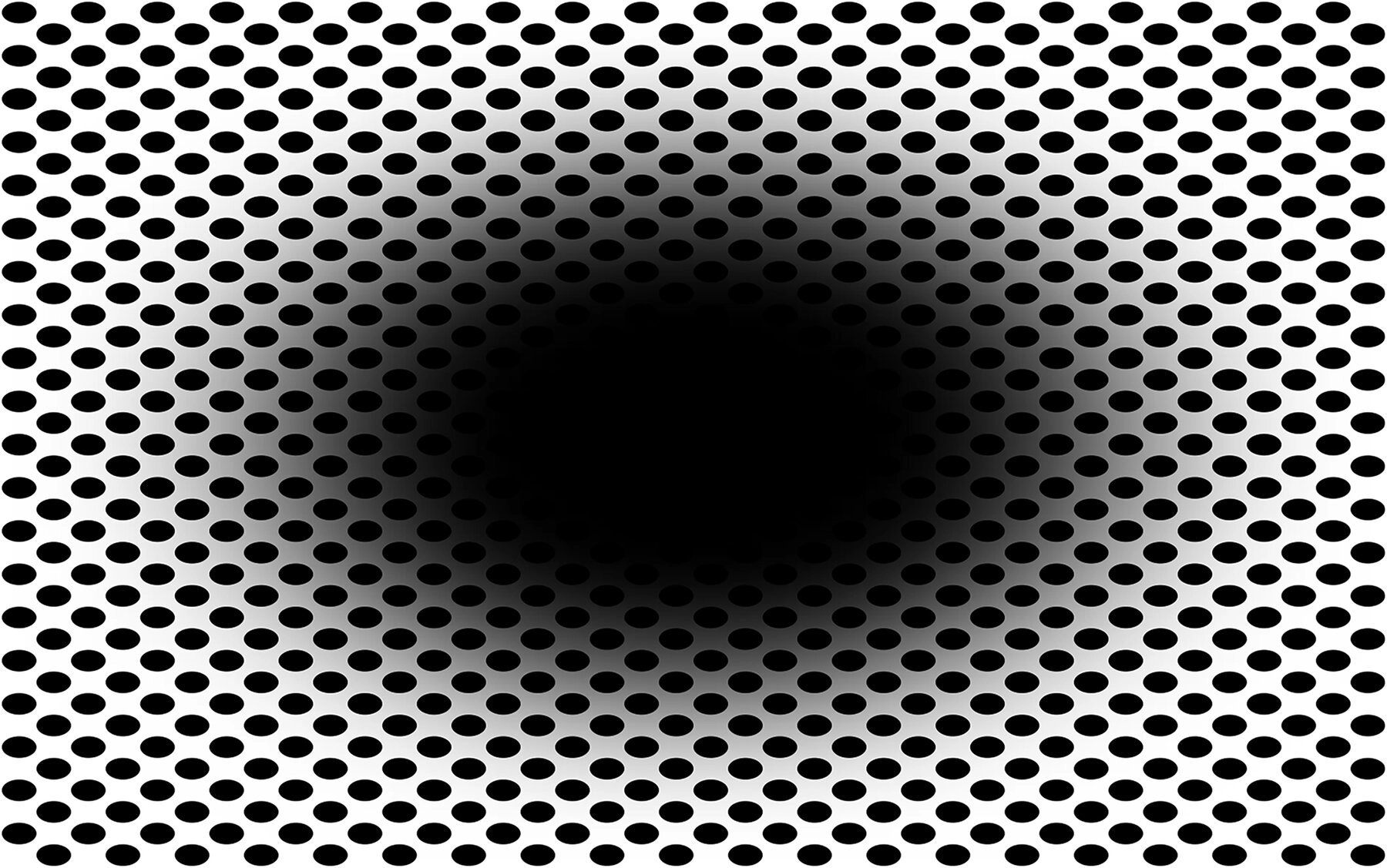

Ambiguous Expanding Black Hole Optical Illusion.

Laeng et al., Front. Hum. Neurosci., 2022

According to Ernst Renan, the renowned 19th-century historian of religion and philologist, if the Roman world had not become Christian, it would be Mithraic today. This controversial premise also appears in the futuristic world of Raised by Wolves, and it is perhaps for this reason that the Roman cult of Mithras, known as one of the most popular mystery religions of the ancient world, has remained the central theme of numerous secret societies, new religious movements, scientific historical research and pop cultural phenomena in modern and contemporary society.

A new god emerges

The Roman cult of Mithras arose in mysterious circumstances at the end of the 1st century AD and quickly became one of the most intriguing archaeological cults of the Roman Empire during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98-117). During the Iulius-Claudian dynasty, in the first half of the century, the cult could hardly have had a Roman form, and it was only in the Hellenistic kingdoms that a cult of Mithra-Helios the Sun spread, but it was not identical in iconography or religious content to the Roman version that later appeared in Rome and the northern provinces after 90 AD.

Although some researchers, most recently Attilio Mastrocinque, have dated the emergence of the new Roman cult of Mithras to the time of the Emperor Augustus, most scholars agree that the winds of change must have begun sometime around the time of the Emperor Nero, in the 60s of the century, and that the new cult was already in full form by the 90s. The religious history of these thirty years is very important, since it marks the formative period of the founding group of the cult, which in the case of Christianity lasted from the 30s until the death of Peter and Paul (the Age of the Apostles).

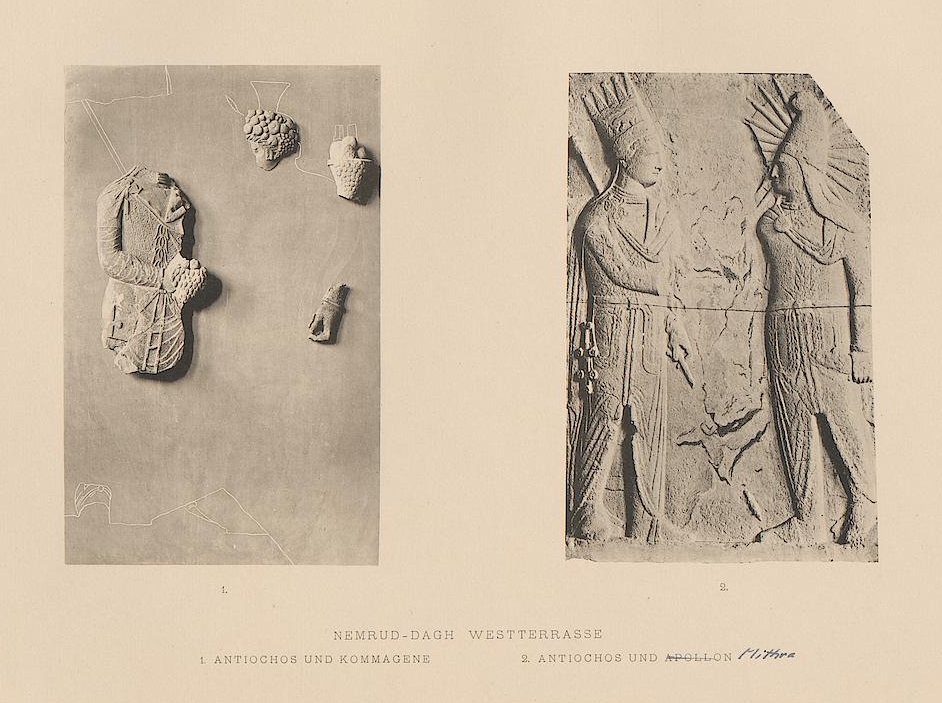

The birth of the Roman cult of Mithras coincides with the arrival in Rome of the Persian imperial elite, but also with the presence in Rome of diasporic communities of noble families from Cilicia and Commagene, while the period between Nero and Trajan sees the intensification of the cultural and political relations that had already existed between the Roman Empire and the Middle East. These links with the East were certainly an important factor, since the new deity, which already appeared in the poem of the poet Statius at the end of the 1st century, was already present in the Roman public consciousness as a Persian-Eastern exotic in its origin story (’the religion founded by Zoroaster’) and in many of its iconographic and linguistic features (Persian trousers, the name of the god Nabarze, nama, the form of greeting nama).

Although this is how this new religious movement was seen and perceived by outsiders, and even by the worshippers of Mithras, the new movement, probably created in Rome, is not Persian, not Zoroastrian, but a so-called bricolage religion, very Greco-Roman in its iconography and visual language, enriched with some of the exotic elements mentioned above, which were essential for the contemporary popularisation of the cult. The method used was therefore that of recreating traditions: bringing the East, considered exotic by the Romans as the world of ancient philosophy, to the West, without breaking with the iconographic and religious traditions with which the Romans were familiar.

The Roman Empire under Trajan. Provinces of earliest mithraic discoveries in purple and red.

Wikimedia

The new deity that appeared on the religious market of the Roman Empire was thus a unique mixture of contemporary Greco-Hellenistic mystery religions, Orphic traditions, Persian exoticism and Neoplatonist doctrines. This cult was a recent product of the cultural fusions and syncretic peculiarities of the Roman Empire (omnipotent gods, pagan monotheistic tendencies, Judeo-Christian-Polytheistic interactions), which spread rapidly in Rome and the Rhine and Danube provinces during the reign of the Emperor Trajan, thanks mainly to the rich and mobile bureaucracy of the military and customs.

Mysteries, secrets and bloody rituals never seen before

The Roman cult of Mithras is characterised by the fact that it once had a heroic story, a central myth, unfortunately no longer known, in which the ancient Romans could learn about the life of Mithras, from his birth from a rock (Mithras Petrogenitus), through his miraculous deeds (Fons Perennis, Transitus Dei), to his bull sacrifice, which gave life and created a new world, opening the gates of the seven spheres to souls, and his triumphant moment of becoming the Sun Goddess. The "story" of Mithras, like the story of Jesus and so many other soteriological, soul-conquering, heroic life stories, then took many forms and was repeated in many versions, as shown by the sculptural and mural sources, which vary from region to region and sometimes from sanctuary to sanctuary, and which, along with written, epigraphic and literary sources, reveal the most about the specificity of this cult.

It is not a central, imperial or universal cult: it does not have a central shrine like the goddess Artemis Ephesia or Iuppiter Dolichenus, its initiation rites are not linked to a central place like the Eleusinian Mysteries, and it does not have large public ceremonies like the cults of Isis, Cybeles or Bacchus. It therefore differs from its contemporary religious rivals in that half of society seems to have been excluded from the cult: women were not supposed to take part in initiation ceremonies, as both literary and epigraphic sources agree. For this reason alone, Renan could not have been right to interpret this religious movement as a rival to Christianity.

Its seven degrees of initiation were cumbersome and complex, provocative or challenging even to the average Roman citizen, excluded women altogether, and carried a discreet religious message known to few, in which an interest in both astronomy and oriental cultures could be justified. Their sanctuaries, now called mithraeums but interpreted as temples or caves of Mithras, were small enclosed spaces in urban buildings or natural caves with ordinary exteriors that provided a space for religious communication for 20-30 people.

Eschewing the opulent specificity and monumentality of the Roman temples, they were spaces lit by lamps, dark and deliberately mysterious, where the internal sacred geography gave the sanctuary its local distinctiveness and appeal. At its height, the cult was known to have hundreds of shrines in almost every city of the empire along its main routes. Hungary is particularly fortunate, as the reconstructed sanctuaries of Fertőrákos and the six sanctuaries of Aquincum (two of which can be visited in the Aquincum Archaeological Park) are the most important legacies of Mithras after Ostia and Rome. Their spectacular reliefs and the almost standard archaeological material of the bull-slaying scene, with its great variety of details, colours and side stories, have linked the cult to mysticism since antiquity.

It was extremely attractive to the Romans (indeed, it is estimated that some 50-60,000 male members of the empire’s fifty million population may have been Mithras worshippers), and sufficiently mysterious to outsiders that ever wilder myths were invented about the Mysteries of Mithras. Early Christian writers in the 3rd and 4th centuries reported bloody sacrifices, orgies and nudity, but these are not supported by archaeological sources. However, the mystical element of initiations, imitating humiliation and rebirth, appears in some Roman wall frescoes and in some rare vases: young men blindfolded and bound, mostly naked or dressed in loose clothes, young men with raven masks carrying food and drink, men with lion masks, one must assume from the painfully scarce sources.

Modern archaeological research on the shrines and the dozens of new Mithras shrines published in recent decades have not only provided a detailed insight into the everyday life of the cult, but have also added a new dimension to Roman religious history and shrine architecture. We now know that bulls were never sacrificed in shrines, that poultry and pigs were widely eaten (sometimes in very large quantities, the preparation of which may have involved logistical challenges and a clear involvement of women), and that each shrine functioned as an individual community, with no central, imperial direction or ’dogma’. Mithras was a glocal cult: a once presumably centrally established cult (with a global, universal message) was most locally validated.

Mithras forgotten, rediscovered and recreated

With the rise of Christianity as the state religion, the Roman cult of Mithras slowly faded away in the late 4th and early 5th centuries AD. Its last shrines in Rome and Ostia were abandoned in the early 5th century, but some shrines were rebuilt and still serve as Christian churches, as the example of the Mithraeum under the famous church of San Clemente shows.

In the Middle Ages, the cult of Mithras was rarely discovered, although there are indications that there were medieval Christian communities that, even in the 12th century, were familiar with the Mysteries of Mithras, or at least with its specific iconographic sources. An example of this is the fresco that can still be seen in the Aula Gotica of the Basilica of the Santi Quattro Coronati, which depicts the slaying of the bull by Mithras, Apollo and other pagan gods in a Christian context.

In the Renaissance, the rediscovery of ancient literary sources and the magnificent reliefs and sculptures unearthed during the great architectural renovations brought the Roman cult of Mithras back into the limelight. The statue of Mithras in the Sala degli Animali of the Vatican Museums, the relief by Ottaviano Zeno or the Borghese relief have already aroused great interest in the Roman cult of Mithras, thanks to the works of Giraldi, Pighius, Ligorio, Lafreri, Beger, Bongarsius, Gruterus, Cartari, Montfaucon and many other Renaissance, Italian, French and German authors of the 16th and 17th centuries. They either saw the cult as a direct Persian export or interpreted it as an allegorical deity of fertility, agriculture or even the possession of Eastern mystical knowledge.

In the lodge books and systems of rules of the Masonic groups that emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Mithras then assumed a surprisingly important role as a discrete but not entirely secret cult, based on initiatory rites and open only to men, which served as a kind of spiritual model for the work of Scottish, English and French Freemasons. However, the Roman Mithras presented there is no longer the ancient deity: he appears as a "re-created" tradition, which can now be interpreted as the result of the cult’s reception history.

Then, in the 19th century, a large number of Mithraic sanctuaries, archaeologically identified and excavated, were found in German territory (Heddernheim), in Ostia, in Transylvania (Marosdécs, Várhely) and in present-day Hungary (Óbuda, Aquincum, Fertőrákos). Some of them had a continental reputation, such as the mithraeums of Heddernheim and Várhely (Sarmizegetusa). Scientific research on the cult also began in the 19th century, notably through the monumental work of Felix Lajard and Franz Valérie Cumont, who for decades defined the methodology of Mithras research with his catalogue of objects created in his twenties and his later numerous published studies, creating the now somewhat misleading category of ’oriental cults’ in Roman religious history.

The 20th century brought many new, well-excavated sanctuaries to Europe and the Middle East, some of which are still the most attractive Roman sites in our archaeological parks and museums. However, it is not only for contemporary community archaeology and museology that this ancient cult, rediscovered half a millennium ago, offers extraordinary perspectives: a particular group of the neo-pagan movements of the 20th century are the new Mithras believers, who appear mainly in Western Europe, the United States and occasionally even in Hungary.

The cult of Mithras is reconstructed and transformed into a living religion by these new-religious, neo-pagan communities, sometimes through fantasy, sometimes through an excellent knowledge of ancient sources. They are part of a movement of hundreds of thousands of people who, at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, have revived ancient polytheistic religious trends.

The cult, which also inspired the neo-pagan movements in Freemasonry, is a constant source of work and resources for contemporary museology and archaeology, and also defines contemporary culture. A number of films, such as Raised by Wolves, have reinterpreted the cult. Although the Mithras group that appears there has little to do with the Roman cult of antiquity, this example illustrates the new and unexplored dimensions that ancient religions can have.

A millennium and a half after the disappearance of the ancient polytheistic cults, the Roman cult of Mithras remains a fascinating subject, not only for researchers, but also for cultural tourism, heritage conservation, new religious movements, secret societies and the pop culture industry. The study of the cult, and more generally the study of Roman religion and its research with new methods, offers many new perspectives, and it would be important for Hungarian scholarship to follow in the footsteps of Károly Kerényi and István Tóth.

References

- Bricault, Veymers, Amoroso et al. (2021) The Mystery of Mithras. Exploring the heart of a Roman cult

- M. Clauss (1990) The Roman cult of Mithras

- László Levente; Nagy Levente; Szabó Ádám (2005) Mithras és misztériumai I-II

- Tóth István (2015) Pannóniai vallástörténet

Comments

Add a comment