Quintus Petronius Felix Marsus

Syndexios in Ostia, his name Marsus suggests that he was a snake-charmer.

Biography

of Quintus Petronius Felix Marsus

- Quintus Petronius Felix Marsus was a syndexios at the Mitreo del caseggiato di Diana.

- Active c. 2nd century in Ostia, Latium, Italia [TNMM 488].

- Active c. early 3rd century in Ostia, Latium, Italia [TNMM 482].

TNMP 102

Marcus Lollianus Callinicus being a father, Quintus Petronius Felix Marsus donated the image of Arimanius and dedicated it.

The name Marsus suggests that this individual was a snake-charmer, who was thought to have occult powers.

In the mithraeum of the Casa di Diana (I,III,3-4) we encounter pater Marcus Lollianus Callinicus. Perhaps it is the same Callinicus, mentioned in a graffito, who was in charge of a hotel in the neighbouring Casa di Giove e Ganimede (I,IV,2). On a few occasions he was acting together with a certain Petronius Felix Marsus, and together they dedicated a depiction of the Persian deity Arimanius (Ahriman), who played a role in the cult of Mithras as manifestation of Hades. The name Marsus suggests that this individual was a snake-charmer, who was thought to have occult powers. Perhaps information that is better withheld from the many tourists who happily stroll on the road in front of these houses, leading to the Capitolium.

—Ostia-antica.org (2020) Famous people in Ostia and Portus: the ancient Greeks

The marsi

The marsi were in origin a tribe or racial group inhabiting the central, mountainous area of Italy, the Abruzzi. They had a reputation, well deserved, for being wild and warlike, for they were only incorporated in the Roman state after a series of long and bitter campaigns in the fourth century BC. Life in the Abruzzi is hard even today among the mountains and forests, and in antiquity it must have been even harder. Its inhabitants lived in poverty, in houses that offered little shelter from the rain, consoling themselves for their indigence with strange and archaic religious practices, and with a little banditry on the side. Their image in classical literature was a bad one, and, although they made excellent soldiers for the Roman legions, of their civilian activities only one stands out – their role as snake hunters, snake charmers and druggists. They were possessed of almost legendary magical powers: they could sing a snake to sleep and extract its venom, they could allow the most poisonous of snakes to rest inside their tunics, and they alone had a store of knowledge about poisons and venoms. Their reputation was such that their tribal name of marsus became the regular Latin equivalent of ‘snake-charmer’, and even of poisoner. These were marginal men, in more than one sense, halfway between civilization and savagery, between expert and quack, between bringer of health and minister of death.

They could come down for a while to the city: Galen talks of seeking out the marsi in Rome to give him advice about poisons and on the various snakes to include in an antidote. He expects his friend Glaucon to have seen them in action there, cutting off the heads and tails of snakes, skinning and gutting them, and then washing the flesh (I.143). But they were rarely resident for long. They were to be found on the road, circulatores, the ‘travelling people’, and at the local markets, dragging in the crowds with displays of daring – hence another name for them, ‘crowd-puller’.

[…]

One must imagine the marsus standing in the market place, brandishing his wooden box of snakes, talking twenty to the dozen, screaming out his wares at the top of his voice, displaying his ‘volubilitas orandi‘, as Quintilian put it, in a high-pitched and grating screech. He might indeed bring help and comfort to the sick: Galen reports without qualm the antidote of Simmias the ‘crowd-puller’ against the tarantula and other poisonous insects, as well as that of Chariton, another traveling salesman, who ‘used on his way round the fairs a remedy against snake bite made from the fruit of spondylium, and catmint, pounded and mixed together in wine, to be drunk several times a day’.

—Vivian Nutton (1985) The Drug Trade in Antiquity

References

- Ostia Antica (2020) Regio I - Insula III - Mitreo del Caseggiato di Diana (I,III,3-4)

Mentions

Fragment with inscription to Arimanius Casa di Diana

TNMM 482

The image of the god Arimanius to which this monument refers has not yet been found.

Inscriptions of Caseggiato di Diana

TNMM 488

This marble slab found near the Casa de Diana in Ostia bears two inscription with several names of brothers of a same community

M. M. Caer[ellius Hiero]/nimus et C[allinic]/us sacerdo[tes et antisti]/es Solis [invic[ti] Mithrae] / thronum / fec[erunt].

Marcus Caerellius Hieronimus and Marcus Caerellius Callinicus, priests and antistes of Sol invincible Mithras, made the throne.

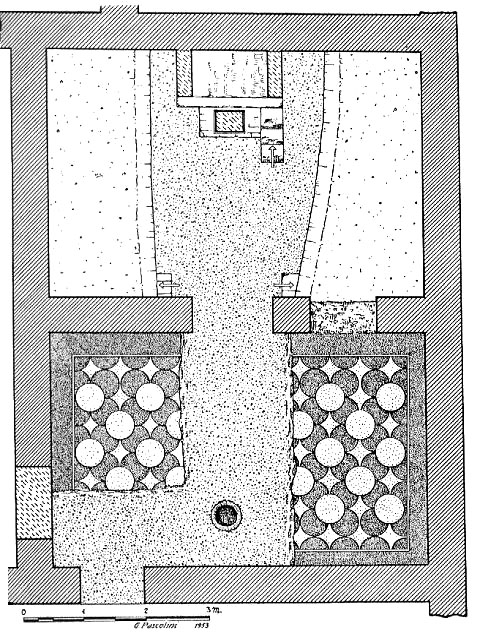

Mitreo del caseggiato di Diana

TNMM 5

The Mithraeum of the House of Diana was installed in two Antonine halls, northeast corner of the House of Diana, in the late 2nd or early 3rd century.